Reading Time: 6 minutes | Category: PostgreSQL Internals | Difficulty: Intermediate

Introduction: The Time-Traveling Journal That Saved Your Relationship with Data

Picture this: it’s 3 a.m., your database server hiccups, and suddenly your entire production instance is on life support. But instead of panic, you calmly restart PostgreSQL and watch it replay the last 47 seconds of transactions like some kind of digital detective solving a crime scene backward. Welcome to the magic of Write-Ahead Logging (WAL) — the most boring-sounding feature that is actually the unsung hero keeping your data safe while you sleep.

If PostgreSQL were a superhero, WAL would be the loyal sidekick who does all the behind-the-scenes work without demanding applause. It’s the diary PostgreSQL keeps of every single change made to your database — except unlike your actual diary, it actually prevents relationship disasters. Think of it this way: before WAL is written to disk, no changes are made to the actual data files. It’s the “write the apology letter before hitting send” feature for databases.

In this post, we’ll time-travel through PostgreSQL’s backup and recovery evolution, from the humble origins of WAL in version 7.1 to the sophisticated features in PostgreSQL 17 that make DBAs’ dreams of effortless recovery a reality.

The Ancient History: PostgreSQL 7.1 and the Birth of WAL

Let’s rewind to 1999. PostgreSQL version 7.1 introduced Write-Ahead Logging and fundamentally changed how the database engine stayed safe during crashes. Before WAL, if PostgreSQL crashed, you’d lose all uncommitted changes sitting in memory. Yikes.

The core concept was simple but revolutionary: write first, execute later. Every change gets recorded in a sequential log on disk before it modifies the actual data files. If the system crashes, PostgreSQL can replay the log and restore to consistency. No data loss (theoretically). No all-nighters debugging corruption. It was the dawn of a new era.

In version 7.1, there was a parameter called wal_files that pre-created WAL files during checkpoints. If you set it wrong, you’d get weird behavior. If you set it right, DBAs felt like wizards. By version 7.3, the developers realized this was overcomplicating things and invented automatic WAL segment pre-generation instead. Crisis averted.

The “aha moment” for early adopters: WAL meant crash recovery went from “pray to the database gods” to “automated and reliable.”

The Evolution: Replication, PITR, and the Birth of Modern Backups

Fast-forward to PostgreSQL 8.0 and beyond. WAL evolved from a mere crash-recovery feature into the backbone of Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR) and Streaming Replication.

With PITR, you could restore your database to any moment in time (down to the transaction) as long as you had archived WAL files. Imagine: “Boss wants to know what the database looked like last Tuesday at 14:47?” Done. You’d use pg_basebackup, configure archive_command to copy WAL files to a safe location, and you’d have a complete audit trail.

For replication, WAL became the message format between primary and replica servers. Instead of copying entire tables, the primary ships WAL records to standby servers, which replay them. Beautiful, efficient, and the foundation of high-availability PostgreSQL.

The gotcha moments DBAs faced:

- Setting

archive_commandtocpand wondering why everything broke when the destination disk filled up. - Misconfiguring

wal_level=minimalthen crying because PITR stopped working. - Forgetting to rotate archived WAL files and slowly drowning in disk usage.

WAL Archiving: The Love-It-Or-Lose-Everything Feature

Here’s where it gets spicy. WAL archiving is the mechanism that copies filled WAL segments (usually 16MB each) to a safe location — S3, NFS, your uncle’s backup server, wherever. Without it, your WAL files stay in pg_wal/ and eventually get recycled as the database creates new ones.

In older PostgreSQL versions, you’d configure archive_command like this:

basharchive_command = 'cp %p /backup/wal_archive/%f'

This tells PostgreSQL: “After each WAL segment fills up, execute this command.” Sounds simple? Here’s what could go wrong:

- Disk full at destination: Archive fails silently, database keeps WAL files, and eventually

pg_wal/fills up, crashing your database. - Permission issues: Archive command runs as the

postgresuser, but your backup location has restrictive permissions. Archive fails. Again. - Timing issues: Archive command takes too long, and PostgreSQL’s archiver process queues up, creating a bottleneck.

Modern DBAs know the drill: use wal_level = replica (or logical if you need it), enable archive_mode = on, and monitor pg_wal/archive_status/ obsessively.

Pro tip for new DBAs: PostgreSQL 15 introduced WAL archive modules (like basic_archive), which are loadable libraries instead of shell commands. They’re more reliable, safer, and have built-in file verification. Use them. Seriously.

The Modern Era: PostgreSQL 14–17 and the WAL Renaissance

Today’s PostgreSQL has evolved into something sophisticated. Here are the features that make DBAs smile:

WAL Levels and Logical Decoding

WAL comes in three flavors:

minimal: Just crash recovery, smallest WAL volume. For dev environments.replica: Crash recovery + replication + PITR. The safe default.logical: Everything above, plus information needed for logical decoding.

Logical decoding is the wizardry that lets you extract database changes as a stream of SQL-like statements or JSON. It powers tools like Debezium for change data capture, allowing you to feed PostgreSQL changes into Kafka, data lakes, or other systems. It’s the “make your database events available everywhere” feature.

WAL Summarizer (PostgreSQL 17)

Version 17 introduced the WAL Summarizer, a background process that tracks changed blocks and writes summaries to pg_wal/summaries/. This powers incremental backups by telling pg_basebackup exactly which blocks changed since the last backup, without scanning all WAL files manually. It’s like your database saying, “Hey, only these blocks changed. You’re welcome.”

Replication Slots and Logical Replication

Replication slots are bookmarks that say, “Don’t recycle this WAL file yet — consumer X still needs it.” This enables:

- Logical replication between PostgreSQL instances (even different versions!)

- CDC (Change Data Capture) pipelines

- Streaming data to third-party systems without writing custom code

The catch? Slots hold onto WAL files, so if a consumer falls behind, your pg_wal/ directory can balloon. Monitor slots with:

sql >SELECT * FROM pg_replication_slots;

Monitor aggressively. Seriously.

Best Practices for Modern WAL Management

If you’re running PostgreSQL 14+, here’s your checklist:

- Set

wal_level = replica(unless you need logical decoding). - Enable archiving with

archive_mode = onand a reliable archive module or command. - Monitor WAL accumulation — create alerts if

pg_wal/grows beyond a threshold. - Use incremental backups with

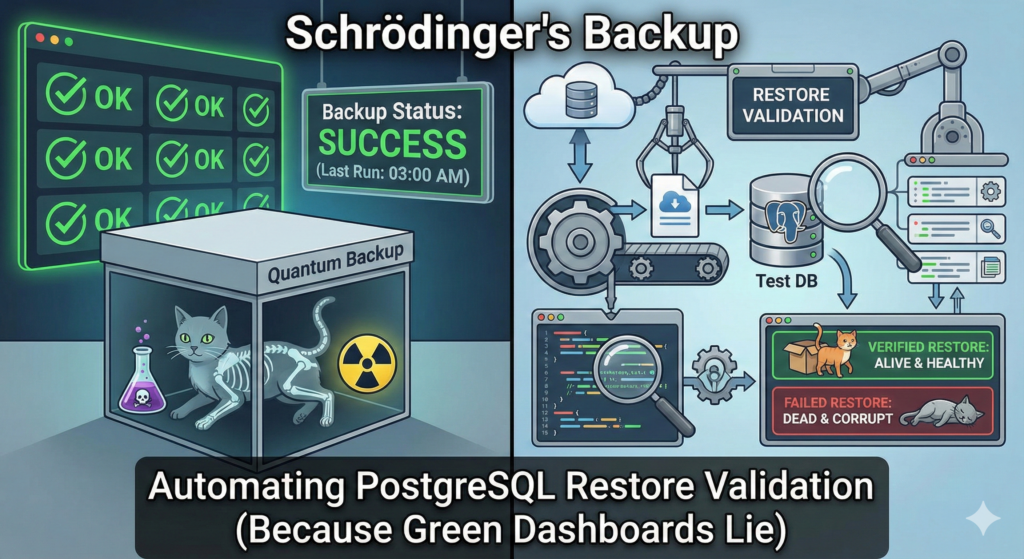

pg_basebackup --incremental(v17+) to leverage WAL Summarizer. - Test recovery procedures regularly. An untested backup is a backup that doesn’t work.

- If using replication slots, monitor them obsessively to ensure consumers don’t lag.

The Punchline: Why WAL Is Your Best Friend

WAL is the reason your 2 a.m. crash doesn’t become a career-defining disaster. It’s the reason PostgreSQL is trusted by companies handling billions of transactions. It’s the reason you can confidently promise “zero data loss” to your boss.

Sure, it’s not sexy. You won’t see it in marketing materials. But it’s there, working silently in pg_wal/, writing transaction after transaction, just in case the universe decides to send a meteor through your data center.

WAL is PostgreSQL’s diary, PITR is your time machine, and if you ever forget to archive it, you’ll earn a special place in DBA hell next to the person who used DROP TABLE without backups.

Respect the WAL. Archive the WAL. Love the WAL.